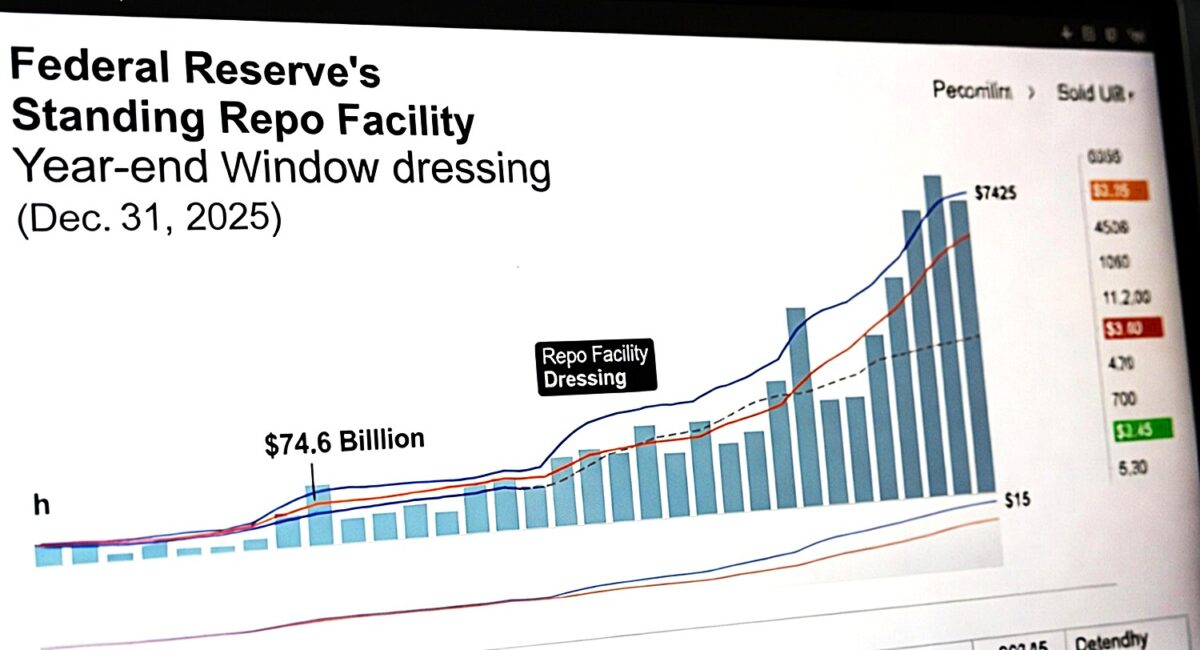

On December 31, 2025, eligible financial firms borrowed an unprecedented $74.6 billion from the Federal Reserve’s Standing Repo Facility (SRF) — the highest usage since the facility’s launch — as banks and dealers managed seasonal year-end liquidity demands, collateral pressures, and regulatory balance-sheet reporting. This surge, driven by typical year-end pressures and encouraged by Fed policy adjustments, was not an abrupt crisis but a reflection of the way U.S. short-term funding markets adjust at calendar turning points.

The Federal Reserve’s Standing Repo Facility (SRF) saw record use on December 31, 2025, as financial firms borrowed $74.6 billion collateralized by Treasury and mortgage-backed securities to handle year-end funding stresses, while reverse repo deposits also surged — a clear sign of temporary market liquidity dynamics rather than structural failure.

Why This Matters Right Now

In routine reporting circles, year-end liquidity spikes often look dramatic — and this one did, hitting a record — but there’s context that market participants and policymakers have been watching closely:

- SRF Usage Jumped: The $74.6 billion figure on the last trading day of 2025 exceeded the prior record of approximately $50.35 billion seen on October 31 (a quarter-end), underscoring how the final calendar day can amplify liquidity needs.

- Collateral Breakdown: Loans were backed by roughly $31.5 billion in U.S. Treasury securities and $43.1 billion in mortgage-backed securities, a technical but important detail — it shows where banks were willing to pledge assets for short-term cash.

- Reverse Repo Participation Also Climbed: While firms tapped the SRF for cash, they also parked a record $106 billion into the Fed’s reverse repo facility, a sign that some cash was abundant and simply being managed back into the system for a return.

- Short-Term Rates Held Steady: Despite the record, repo market rates (including SOFR) remained reasonably contained — typical of market responses when the Fed’s backstop tools function effectively.

The Standing Repo Facility Explained

What Is an SRF Operation?

A standing repurchase agreement (repo) is a contract where the Fed lends cash overnight in exchange for high-quality securities as collateral (Treasuries, agency debt, mortgage-backed securities). The borrower agrees to repurchase the securities the next day. This mechanism:

- Helps institutions meet cash needs,

- Supports the Fed’s interest-rate control framework,

- Smooths short-term funding markets when private lenders pull back.

Policy Framework Behind SRF

As per Federal Reserve operational guidance, the SRF conducts daily overnight operations (typically morning and afternoon) with set limits and rates. Eligible counterparties — primarily large banks and primary dealers — can bid for funds against eligible collateral at a minimum bid rate usually near benchmark rates.

Year-End Funding Markets — Why Liquidity Needs Spike

Balance–Sheet Reporting Pressures

At quarter and year ends, banks often trim assets (or reclassify) to satisfy regulatory capital and leverage requirements. That can temporarily pull cash out of circulation, forcing firms to secure funds quickly — hence repo demand.

Seasonal Patterns

Historically, markets see:

- Higher demand for short-term cash late in a quarter/year,

- Rising repo rates as dealers adjust portfolios,

- Corresponding balance back into reverse repo once institutions satisfy internal targets.

This 2025 event fits that profile.

SRF vs. Other Fed Tools

Standing Repo vs. Reverse Repo

- SRF: Fed lends cash against collateral to ease funding strains.

- Reverse Repo: Financial entities park cash at the Fed, effectively absorbing excess liquidity.

Both are plumbing tools for money markets but operate in opposite directions. The simultaneous high use of both on December 31 suggests active balance-sheet positioning, not just stress.

SRF Relative to Overall Money Markets

Despite the record SRF number, it remains small compared to daily tri-party repo market volumes, which often exceed $1.3 trillion — so even a $74.6 billion draw isn’t a fundamental surge in overall market dependence.

What Analysts Are Saying

Experienced market watchers are split in tone — but most lean toward this being operational behavior, not a looming crisis:

- Routine Interpretation: Traders, lenders, and even the Fed staff point to year-end bookkeeping and portfolio adjustments as the main cause.

- Risk Perception: Some observers note that sharp moves in SRF usage can indicate tougher funding conditions — but that needs to be measured over multiple days/weeks, not a single end-of-period spike.

- Policy Implication: The Fed lifting internal caps on repo usage (earlier in 2025) was intended to give markets flexibility — likely contributing to larger year-end take-up.

Market Reaction — Real Price Moves

Equity markets and bank stocks showed modest reactions:

- Bank Stocks Softened Slightly: Some lenders like Bank of America and Goldman Sachs saw mild dips, likely tied more to broader thin holiday trading and rate expectations rather than pure repo demand.

- Broader Indices Muted: With key macro catalysts like U.S. jobs data and January Fed meetings ahead, repo dynamics were only one of many influences on asset prices.

What Comes Next — 2026 and Beyond

Looking forward:

- Normalization Expected: Year-end spikes almost always ease as January trading begins and balance sheets “reset.”

- Watch for Patterns: Persistent or repeated larger repo draws outside quarter/year ends would be more alarming; single date spikes are usually administrative.

- Policy Signals: Fed’s January 2026 meeting outcomes on rates and balance-sheet strategy could shift how the markets price short-term funding going forward.²

Conclusion — What This Record Really Means

Here’s the honest assessment from someone who’s tracked repo markets through the 2020s:

This record SRF usage was noticeable and important, but it’s not a standalone sign of systemic collapse. Instead, it reflects how seasonal forces, regulatory reporting, and available Fed tools interact at the tail end of a trading year. The real market test won’t be one day’s numbers — it’ll be how these facilities are used in normal market conditions throughout 2026.

In other words: the plumbing creaked, but it didn’t burst. — Senior Markets Editor